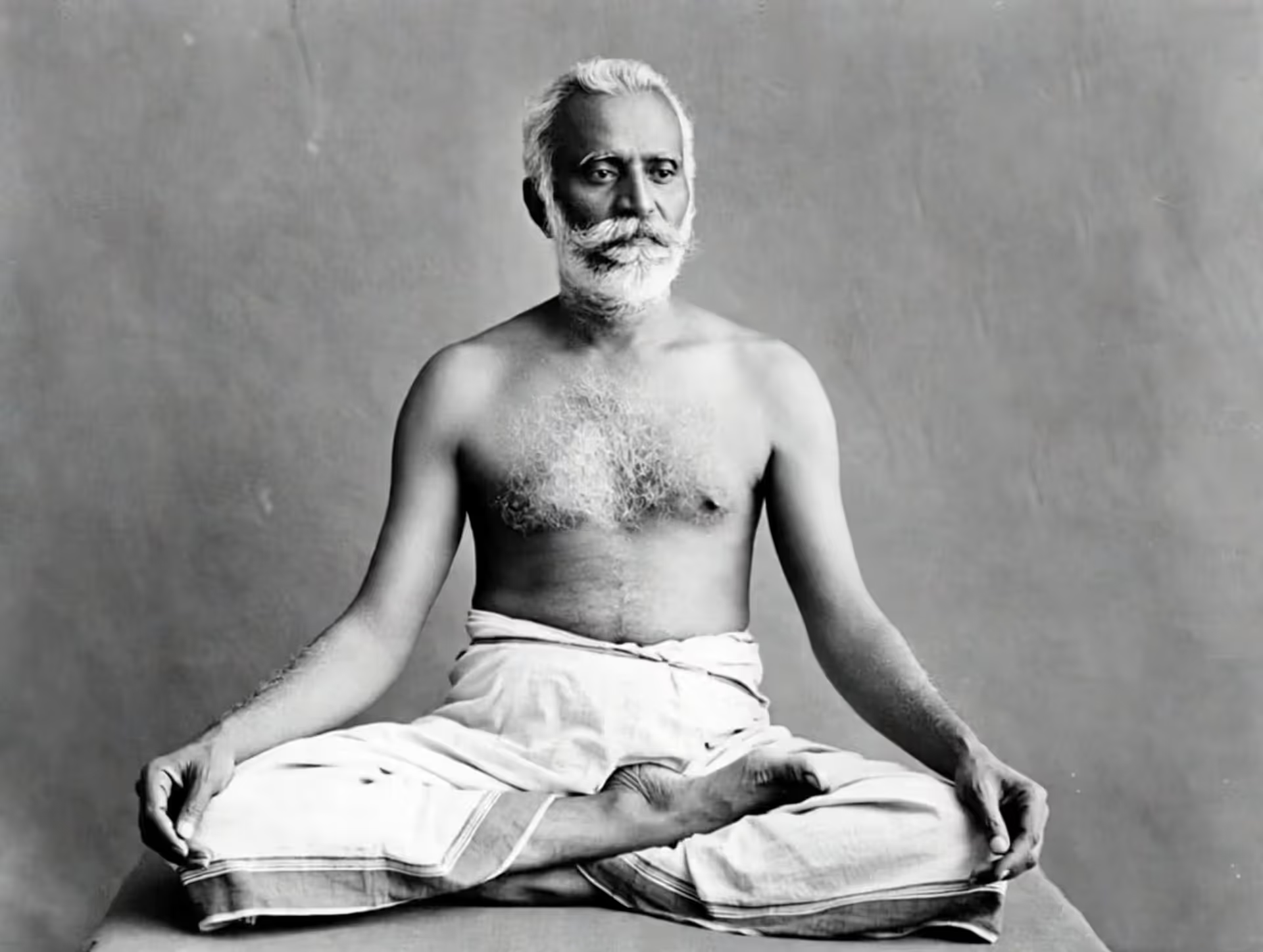

Archival portrait of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya seated cross-legged.

Krishnamacharya: The Teacher Who Shaped Every Yoga Style You've Practiced

Walk into any studio in the United States — vinyasa flow in Brooklyn, Ashtanga in San Francisco, Iyengar alignment in Denver, a gentle therapeutic session at a physical therapy clinic in Houston — and the practice you encounter traces back, through a surprisingly short chain of teachers, to one person. Not a brand. Not a corporation. A single South Indian Brahmin scholar who taught for over seven decades and never sought international fame.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989) didn't invent yoga. But he reorganized, systematized, and personalized it in ways that made every contemporary Western practice possible. Understanding his biography, how his methods evolved, and why his students created such radically different styles answers a question most practitioners never think to ask: where did all of this come from?

Who Was T. Krishnamacharya? (1888–1989)

Born in 1888 in Muchukundapuram, a village in what is now Karnataka, Krishnamacharya came from a lineage of Vaishnavite Brahmins — a family embedded in Sanskrit scholarship and Vedic ritual. Any serious account of T. Krishnamacharya's biography starts with this foundation: his early education was classical, rooted in the yoga philosophy origins that most Western practitioners never encounter. He studied Sanskrit grammar, Vedic chanting, logic, and Hindu philosophy at institutions across South India, eventually earning degrees in all six darshanas (schools of Indian philosophy) — a credential almost unheard of even among scholars of his era.

The pivotal chapter of his training remains partly legendary: a reported seven-year period of study under a teacher named Ramamohan Brahmachari near Lake Manasarovar in Tibet, where he learned asana, pranayama, and the therapeutic application of yoga to individual constitutions. The historical details of this period are unverifiable — no independent documentation exists — but the methods he brought back to India were demonstrably different from anything being taught publicly at the time.

In the 1930s, the Maharaja of Mysore, Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV, invited Krishnamacharya to teach at the Mysore Palace. This patronage gave him resources, students, and institutional support to develop his approach over two decades. After the patronage ended in the early 1950s, he relocated to Chennai (then Madras), where he taught privately until his death at age 100 in 1989.

The "father of modern yoga" label is both deserved and slightly misleading. Deserved because his direct students created the dominant global styles. Misleading because it implies he originated the tradition rather than radically reshaped it. He was a reformer and synthesizer — brilliant at bridging ancient texts with practical application — not a founder in the way the title suggests.

What Krishnamacharya Actually Taught (and How It Changed Over 70 Years)

The Mysore Palace Period (1930s–1950s): Athletic, Demanding, Group-Oriented

Author: Ava Mitchell;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

Under palace patronage, Krishnamacharya taught primarily young men and boys — including the Maharaja's family members. The instruction was vigorous: demanding sequences of linked postures performed with synchronized breath, often in groups. Demonstrations included extreme feats — stopping his pulse, holding postures for extended durations — designed partly to generate public interest in yoga at a time when the practice had little cultural prestige among urban Indians.

The sequences from this period became the foundation of what Pattabhi Jois later codified as Ashtanga Vinyasa. Dynamic, physically challenging, and relatively standardized — designed for fit, young bodies with the goal of building strength, discipline, and heat.

The Chennai Period (1950s–1989): Therapeutic, Individualized, Breath-Centered

After losing palace support and relocating to Chennai, Krishnamacharya's student population changed dramatically. Instead of athletic teenagers, he worked with adults managing chronic illness, aging bodies, respiratory conditions, and injuries. His methodology shifted accordingly.

The Chennai work centered on one-on-one instruction tailored to the individual — not a class format. Breath became the primary tool, with asana serving as a vehicle for respiratory regulation rather than an athletic end in itself. Sequences were shorter, gentler, and designed around the student's specific therapeutic needs.

This transformation is the key to understanding Krishnamacharya's teachings: he didn't teach a system. He taught principles — primarily vinyasa krama (the intelligent sequencing of breath and movement) and the adaptation of practice to the individual — and applied them differently depending on who stood in front of him.

Author: Ava Mitchell;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

Four Students, Four Global Styles: How Krishnamacharya's Lineage Built Modern Yoga

The yoga lineage history of the 20th century runs directly through Krishnamacharya's students. That a single teacher produced four radically different global traditions is the strongest evidence of his foundational principle: teach the person, not the method.

| Student | Years with Krishnamacharya | Style Founded | Core Principle Inherited | Key Departure from Teacher | Global Reach Today |

| K. Pattabhi Jois (1915–2009) | ~1930–1953 | Ashtanga Vinyasa | Breath-linked sequential movement (vinyasa krama) | Codified fixed sequences; teacher rarely modified for individuals | Major global presence; Mysore-style studios in 50+ countries |

| B.K.S. Iyengar (1918–2014) | ~1934–1937 (intermittent) | Iyengar Yoga | Precision of alignment, therapeutic application | Introduced extensive prop use; developed detailed anatomical pedagogy | Largest formal certification system; studios worldwide |

| Indra Devi (1899–2002) | ~1937–1939 | Accessible popularization (no branded style) | Yoga is for everyone, regardless of age or gender | Taught primarily in the West; removed esoteric and Sanskrit framing | Introduced yoga to Hollywood, China, Argentina; opened access for women |

| T.K.V. Desikachar (1938–2016) | Lifelong (son of Krishnamacharya) | Viniyoga | Individual adaptation; breath as primary tool | Maintained the therapeutic, one-on-one model his father evolved into | Strongest in therapeutic and clinical settings; Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM) |

The divergence among these four students isn't a contradiction — it's a direct expression of what they each received. Jois studied during the vigorous Mysore period and crystallized its athletic approach. Iyengar, whose early training was brief and reportedly harsh, developed his own precision methodology partly in response to that experience. Devi studied as an adult woman in the late 1930s — already an anomaly — and carried forward the accessibility principle. Desikachar, as Krishnamacharya's son, witnessed the full evolution and inherited the mature, therapeutic framework of the Chennai years.

Yoga is the process of uniting the body, mind and breath.

— T. Krishnamacharya

Krishnamacharya's Influence on Hatha Yoga as Practiced Today

Hatha yoga — posture-based physical practice — existed for centuries before Krishnamacharya. Texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century) and the Gheranda Samhita (17th century) describe asanas, pranayama, and purification techniques. But the history of hatha yoga as practiced in American studios bears only a partial resemblance to those medieval sources.

He reshaped what "doing yoga" meant in practical terms. Specific contributions that define modern practice:

The linking of breath to movement as a structural principle. Before him, asana and pranayama were typically taught as separate disciplines. He integrated them into a single flowing methodology — the concept now called "vinyasa" in every studio schedule in the country.

Sun Salutation sequences as a foundational warmup. Surya Namaskar existed before Krishnamacharya, but he systematized and popularized its integration into the beginning of practice — now so universal that most practitioners assume it was always central to yoga.

The concept of modifying postures for individual bodies. While Iyengar developed the prop system (blocks, straps, blankets, chairs), the underlying principle — that the pose should serve the person rather than the person serving the pose — came directly from Krishnamacharya's therapeutic framework.

The treatment of yoga as a health intervention, not solely a spiritual discipline. His Chennai-period work with chronic illness, respiratory conditions, and aging bodies laid the groundwork for today's clinical yoga therapy movement.

Contested Legacy: What Critics and Scholars Debate

Author: Ava Mitchell;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

Honest engagement with Krishnamacharya's legacy requires acknowledging the scholarly questions that emerged in the 2000s.

Researcher Mark Singleton, in his 2010 book "Yoga Body," presented evidence that the vigorous Mysore-period sequences may have incorporated elements of European gymnastics, Indian wrestling (mallakhamb), and British military calisthenics — physical culture traditions circulating in early 20th-century India. The implication: the "ancient" asana sequences may be significantly more modern and culturally hybrid than their presentation suggests.

This research doesn't diminish Krishnamacharya's contribution. It contextualizes it. He was operating in a period of intense cultural exchange and nationalist revival, where Indian educators were actively synthesizing indigenous and Western physical practices. If he incorporated gymnastics into his teaching — and the visual parallels between Mysore-period sequences and Danish gymnastics drills are genuinely striking — he did so with a depth of philosophical and respiratory integration that transformed the source material into something fundamentally different.

The tension between devotional accounts (Krishnamacharya as a vessel for unbroken ancient tradition) and historical scholarship (Krishnamacharya as a brilliant creative synthesizer) remains unresolved. For practitioners, the most useful framing is probably this: the value of the practices he transmitted doesn't depend on their age. What matters is whether they work — and seven decades of global practice suggest they do.

It is not the person who must adapt to yoga, but yoga that must be adapted to the person.

— T. Krishnamacharya

Why Krishnamacharya Still Matters If You Practice Yoga in 2026

His core principle — adapt the practice to the individual standing in front of you, never force the individual into the practice — remains the most important idea in yoga instruction. Every time a teacher offers a modification, suggests a prop, or adjusts a sequence for a student's knee injury, they're operating from a framework Krishnamacharya developed. Every time a class offers "options at each level," that pedagogical choice has a direct lineage.

The Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM), founded by Desikachar in Chennai, continues to teach, research, and train teachers in the therapeutic tradition. It remains one of the few institutions worldwide that emphasizes the individualized, breath-centered methodology of Krishnamacharya's later years — the work he considered his most refined.

For the average American practitioner, recognizing this history doesn't change the daily experience of class. But it does provide context. The vinyasa flow you do on Tuesday evenings, the Iyengar precision workshop on Saturday mornings, the gentle restorative session your physical therapist recommends — all of these carry the fingerprints of a scholar who spent a century refining the relationship between breath, body, and attention. Knowing the source doesn't change the practice. It does deepen your understanding of why it works.

FAQ

Krishnamacharya's legacy isn't a fixed method or a branded style — it's a principle: meet the student where they are and adapt the tools accordingly. That idea, more than any specific sequence or posture, is what traveled from a palace in Mysore and a small room in Chennai to every studio, gym, and therapy clinic where yoga is taught today. Knowing his name isn't required to benefit from the practice. But understanding his work illuminates why the tradition is as diverse, adaptable, and alive as it is.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on yogapennsylvania.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share yoga tips, meditation practices, wellness guidance, retreat experiences, and lifestyle insights, and should not be considered medical, therapeutic, fitness, or professional health advice.

All information, articles, images, and wellness-related materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Individual health conditions, physical abilities, wellness goals, and experiences may vary, and results can differ from person to person.

Yogapennsylvania.com makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to consult qualified healthcare or wellness professionals before beginning any new yoga, meditation, or fitness practice.