Millions practice yoga worldwide, yet few have explored the Yoga Sutras—the ancient text that defines yoga as far more than stretching and breathing exercises. This philosophical framework presents yoga as a comprehensive approach to mental discipline, conscious living, and inner transformation rather than simply physical movement.

Who Is Patanjali?

Historical records offer limited concrete information about Patanjali, leaving his identity shrouded in scholarly uncertainty and spiritual legend. His primary legacy lives through the Yoga Sutras, where he organized yogic wisdom into an accessible structure. Everything else about his life remains largely speculative.

Various traditional stories describe Sage Patanjali differently across regions and time periods. Certain texts present him as a polymath who contributed to Sanskrit linguistics and traditional medicine alongside his yogic work. Alternative narratives portray him as a semi-divine being—often shown with a snake's lower body and human upper torso. These symbolic representations complicate efforts to distinguish actual historical details from mythological storytelling.

Dating Patanjali places him roughly between 200 BCE and 400 CE, though academic consensus remains elusive on precise timing. Evidence suggests he gathered and structured pre-existing practices rather than creating yoga from nothing. Pinpointing dates for ancient Sanskrit literature proves notoriously difficult since oral traditions predated written manuscripts by many generations, and physical texts from early periods haven't survived.

Both mythological and historical interpretations provide meaningful perspectives. As a historical figure, Patanjali probably functioned as a scholar who brought coherence to diverse yogic teachings. As mythological symbol, he embodies timeless wisdom transcending individual identity. Either reading supports the text's practical applications for consciousness work and mental cultivation.

The impact of his systematization reverberates through centuries and across continents. His compilation became the definitive classical reference for yogic thought, studied by ancient lineages and contemporary teacher certifications alike. Without this organizational work, yoga practices might have remained fragmented techniques rather than unified methodology.

Who Wrote the Yoga Sutras?

Author: Lily Patterson;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

Traditional sources unanimously credit Patanjali with authorship, though this straightforward answer masks considerable complexity. Ancient Indian literary culture prioritized knowledge preservation and transmission over individual attribution in ways that differ sharply from Western authorial conventions.

Academic discussions continue examining whether a single individual crafted the complete work or if "Patanjali" represents collaborative efforts under one identifying name. Certain scholars observe stylistic inconsistencies between sections that could indicate multiple contributors. Others emphasize the text's overall unity as supporting single authorship.

The compilation versus authorship question illuminates how ancient texts evolved. Patanjali presumably collected existing yogic wisdom, arranged it systematically, contributed interpretive elements, and formatted everything as sutras. This process makes him editor, compiler, and creator simultaneously. The authorial specifics matter less than recognizing the text synthesizes broad traditional knowledge rather than presenting singular innovation.

Whether Patanjali existed as one historical sage or functioned as a collective identifier for a teaching school doesn't reduce the text's utility. The philosophical content works effectively regardless of who originally assembled it.

What Are the Yoga Sutras? (Overview & Structure)

"Sutra" translates as thread or condensed saying—extremely brief statements designed for memorization and oral transmission. Sanskrit sutras pack dense meaning into minimal language, requiring interpretive commentary and direct teaching for complete understanding. This compression suited educational systems where material passed through recitation and memory rather than written study.

Patanjali's compilation contains 196 compact aphorisms, some consisting of merely a handful of Sanskrit words. Their brevity shouldn't suggest simplicity. Individual sutras carry interpretive depth that scholars have explored for millennia. Surface translations provide basic access; genuine comprehension demands dedicated investigation.

Four distinct chapters (padas) organize the material, each examining particular dimensions of yogic practice and theory:

| Chapter | Sanskrit Name | Focus | Theme |

| 1 | Samadhi Pada | Yoga's essential nature | Consciousness, mental states, foundations |

| 2 | Sadhana Pada | Practical methodology | Eight limbs, applied techniques |

| 3 | Vibhuti Pada | Extraordinary capacities | Advanced absorption, supernatural abilities |

| 4 | Kaivalya Pada | Ultimate freedom | Liberation from conditioning |

This arrangement follows logical progression: establishing definitions, presenting practice methods, exploring advanced attainments, and clarifying final goals. Practitioners typically emphasize the second chapter because it contains the famous eight-limb structure outlining concrete steps.

Patanjali Yoga Sutras Summary (Core Teachings)

Sutra 1.2 stands as the text's most recognized statement: "Yogas chitta vritti nirodhah"—typically rendered as "Yoga means stilling the mind's fluctuations." This foundational definition presents yoga as mental technology rather than gymnastic activity. Minds continuously produce thoughts, emotional reactions, narratives, and evaluations. Yogic practice quiets this internal turbulence.

Chitta encompasses the complete mental apparatus—awareness, unconscious conditioning, memory storage, ego identity, and discriminative intelligence combined into one system. Vrittis describe the continuous modifications or ripples within chitta—perpetual mental activity that colors experience and generates dissatisfaction. Nirodhah indicates cessation or calming. Combined meaning: yoga occurs when mental disturbances settle, revealing fundamental nature.

Five kleshas constitute mental distortions that perpetuate suffering and maintain reactive patterns. Patanjali names them: fundamental ignorance (avidya), ego identification (asmita), craving (raga), rejection (dvesha), and survival fear (abhinivesha). These afflictions motivate behavior and create distress through perceptual distortion. Yogic methodology aims to diminish and eventually eliminate these sources of suffering.

Liberation (kaivalya) emerges through consistent practice that progressively reduces mental turbulence and neutralizes afflictive patterns. Freedom doesn't require withdrawing from existence—it means perceiving circumstances accurately without conditioning-based distortions. Life continues, but suffering caused by clinging, avoiding, and misunderstanding dissolves.

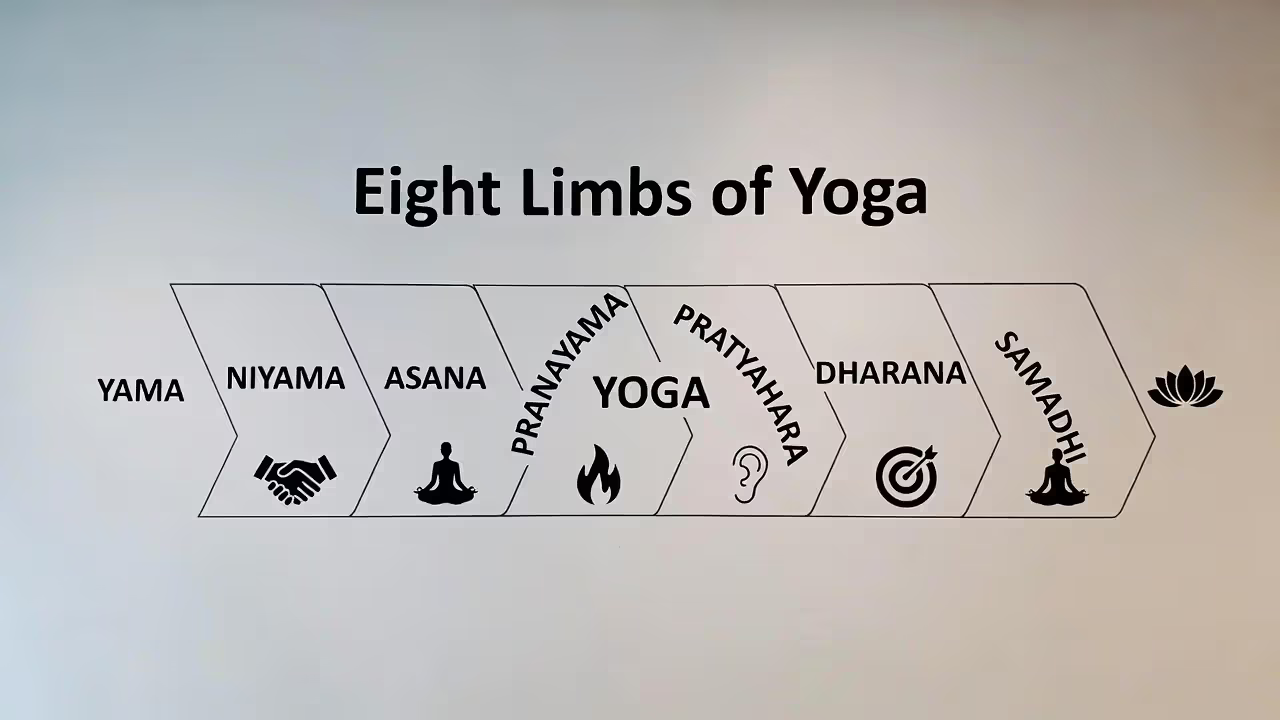

The Eight Limbs of Yoga Explained

Author: Lily Patterson;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

The eight-limb framework (ashtanga) maps practical territory for yogic development. These components function as integrated aspects of unified practice rather than sequential stages. Development happens simultaneously across all dimensions rather than mastering each separately before advancing.

1. Yama (Ethical Restraints)

Yamas establish guidelines for external interactions and worldly engagement. Five principles comprise this category: non-violence (ahimsa), honesty (satya), not taking what belongs to others (asteya), appropriate energy use (brahmacharya), and non-grasping (aparigraha). These function as navigational principles for minimizing harm and friction rather than absolute rules.

2. Niyama (Personal Observances)

Niyamas address internal cultivation and individual behavior. Five observances form this group: purity (saucha), contentment (santosha), self-discipline (tapas), introspective study (svadhyaya), and devotion to something beyond ego (ishvara pranidhana). These qualities create conditions supporting continuous practice.

3. Asana (Posture)

Patanjali characterizes asana as stable, easeful positioning for meditation—quite different from contemporary yoga's elaborate pose sequences. Original intention: conditioning the body for comfortable extended sitting during contemplative practice. Physical training serves this purpose but constitutes only one-eighth of the complete system.

4. Pranayama (Breath Control)

Pranayama encompasses breath manipulation techniques that influence vital energy and consciousness states. Breathing bridges physical and mental dimensions—regulating breath affects both simultaneously. Practices range from simple observation to sophisticated retention sequences, each creating distinct neurological and psychological effects.

5. Pratyahara (Withdrawal of Senses)

Pratyahara involves directing awareness inward rather than remaining constantly reactive to external phenomena. Sensory capacity continues functioning while you develop non-reactivity to stimulation. This attentional shift from outer to inner prepares consciousness for concentrated focus.

6. Dharana (Concentration)

Dharana means sustaining attention on one chosen object—breathing rhythm, verbal formula, visualization, or concept. Mental wandering happens constantly. Concentration practice involves patient redirection each time focus drifts. Repetition gradually strengthens attentional stability.

7. Dhyana (Meditation)

Dhyana arises when concentrated focus maintains itself with reduced effort. Distinction from dharana: concentration requires continuous corrective effort, whereas meditative states flow with greater ease. Attention remains absorbed in the focal point, but maintenance becomes progressively effortless.

8. Samadhi (Absorption)

Samadhi describes experiences where ordinary self-sense temporarily disappears. The perceiver-perceived distinction collapses—no separate "you" observing something external. These absorptive states exist along a spectrum, ranging from initial glimpses to complete realization. Samadhi represents yoga's highest aspiration.

| Limb | Meaning | Modern Application Example |

| Yama | External ethics | Choosing honesty despite personal cost |

| Niyama | Internal discipline | Daily meditation regardless of mood |

| Asana | Physical positioning | Finding comfortable meditation seat |

| Pranayama | Breath work | Managing anxiety through breathing techniques |

| Pratyahara | Sensory withdrawal | Minimizing distractions during deep work |

| Dharana | Focused attention | Maintaining single-pointed task focus |

| Dhyana | Meditative flow | Sustained concentration without strain |

| Samadhi | Complete absorption | Total presence without self-awareness |

Yoga Philosophy Basics for Modern Practitioners

Author: Lily Patterson;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

Contemporary confusion arises from conflating yoga-as-fitness with yoga-as-philosophy. Modern practice spaces emphasize bodily flexibility, muscular strength, and athletic achievement. Traditional philosophical yoga prioritizes mental training, ethical behavior, and consciousness investigation. Both offer benefits but serve distinct purposes.

Recognizing asana as merely one-eighth matters because Western yoga culture frequently treats physical practice as the complete tradition. You can develop impressive physical capabilities without engaging the remaining seven dimensions, but this approach doesn't constitute yoga by Patanjali's standards. Body work prepares for contemplative practice—it's foundational, not final.

Ethics and awareness form yoga's practical base. The yamas and niyamas operate continuously in career situations, personal relationships, and daily challenges. These guidelines function independently of mat-based practice. Simple test: if your yoga doesn't influence interpersonal conduct or stress responses, the philosophical essence remains untapped.

Practical yama application means making countless small choices aligned with non-harm, truthfulness, and non-attachment. Traffic jam scenario—respond with angry aggression (violating non-harm through hostile thoughts) or practice emotional balance? Workplace credit theft—immediate revenge or measured honest communication? These ordinary situations test philosophical understanding more than any balance pose.

Classical Yoga Philosophy vs Modern Yoga

Traditional yogic philosophy prioritizes contemplative practice over physical conditioning. Patanjali allocates three brief sutras to bodily posture while dedicating extensive passages to concentration, meditation, and absorption. This proportion reveals clear priorities: physical work supports mental cultivation, not vice versa.

Spiritual versus wellness orientations create fundamentally different practice relationships. Fitness-focused yoga targets physical health, stress relief, and general wellbeing—legitimate objectives. Spiritually-oriented yoga seeks freedom from mental suffering through consciousness understanding and affliction elimination. Either path has merit, but recognizing the distinction prevents confusion about actual practice goals.

Contemporary influences appear in teacher certifications including philosophical components, studios scheduling meditation sessions, and practitioners exploring dimensions beyond physical postures. The Sutras supply language and conceptual frameworks for discussing yoga's psychological and spiritual territories.

Many physical practitioners eventually feel drawn toward philosophical study and contemplative methods. The body offers an accessible beginning point; deeper teachings become available when readiness develops.

Yoga is the stilling of the fluctuations of the mind.

— Patanjali, Yoga Sutras 1.2

Why Patanjali Still Matters Today

Teacher training programs typically require Yoga Sutra study as part of standard 200-hour certifications. Instructors learn articulating yoga beyond physical cuing, grounding classes in traditional philosophical context. Even when students never encounter technical terminology like "chitta vritti," understanding yoga's mental focus fundamentally shapes instructional approach.

Multiple contemporary styles reference or reinterpret Patanjali's organizational framework. Iyengar methodology emphasizes precise alignment; Ashtanga Vinyasa employs distinct eight-part structuring; Viniyoga adapts techniques to individual circumstances. All acknowledge the Sutras as foundational literature while developing unique practical approaches.

Modern mindfulness practices echo ancient techniques Patanjali described millennia ago. Contemporary mindfulness meditation, cognitive therapy approaches, and stress management programs utilize methods the Sutras systematically outline. These teachings describe consciousness work that remains applicable across cultural or spiritual contexts.

Common Misconceptions About Patanjali and Yoga

Incorrectly crediting Patanjali with yoga's invention overlooks centuries of pre-existing practice traditions. Yogic methods existed in multiple forms long before the Sutras appeared. His contribution involved organizing dispersed knowledge into unified structure, making him systematizer rather than originator.

Reducing yoga to physical exercise alone reflects Western cultural adaptation rather than traditional understanding. Patanjali barely discusses bodily postures. Ethics, breathing, concentration, and contemplation receive far more textual attention than movement sequences.

Treating the Sutras as religious scripture misrepresents their actual function. The text offers practical methodology for mental training and consciousness exploration. Applying these techniques doesn't require adopting Hindu theological positions. The philosophical system operates across belief frameworks as tools for understanding and managing mental phenomena.

Safety, Accessibility & Practical Considerations

Author: Lily Patterson;

Source: yogapennsylvania.com

The Sutras outline an idealized developmental path assuming particular conditions: substantial practice time, supportive circumstances, minimal worldly responsibilities, and probably monastic living situations. Contemporary practitioners navigate employment demands, family obligations, financial pressures, and severely limited time. Applying ancient wisdom to modern circumstances requires thoughtful adaptation.

Certain instructions need careful contextual interpretation. Extreme breath retention, forceful concentration, and severe discipline can create difficulties without experienced guidance. The text presumes teacher-student relationships where seasoned practitioners mentor newcomers through challenges.

Psychological considerations become relevant when working directly with consciousness. Individuals carrying trauma, managing active psychological conditions, or experiencing mental instability should approach advanced contemplative practices cautiously. Quieting mental activity sounds peaceful until previously suppressed material surfaces when usual distractions cease.

Frequently Asked Questions

Patanjali's Yoga Sutras present systematic approaches for understanding and cultivating the mind that retain relevance across millennia. His organizational work transformed scattered yogic teachings into unified philosophy emphasizing mental discipline, conscious living, and awareness exploration beyond physical conditioning.

The eight-limb structure provides applicable framework for contemporary existence even when formal contemplative practice proves impossible. Ethical behavior (yama), personal discipline (niyama), physical preparation (asana), breathing awareness (pranayama), attention management (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and absorption (samadhi) progress together as unified developmental path.

Comprehending classical yogic philosophy clarifies distinctions between ancient consciousness science and contemporary exercise modifications. Physical training holds legitimate value but represents merely one-eighth of the complete system. Philosophical teachings address ethics, mental conditioning, and liberation from suffering—concerns maintaining relevance from antiquity through present day.

Contemporary students benefit from engaging these foundational teachings while adapting them thoughtfully to current contexts. The Sutras describe universal consciousness dimensions and supply practical tools for skillfully working with mental processes. Applying these principles doesn't require adopting ancient cultural forms or religious commitments—the techniques function as applicable psychology for anyone seriously engaging their mental life.

Patanjali's enduring significance derives from organizing rather than inventing yoga. The Sutras provide structure transforming scattered practices into coherent, transmissible system. Whether seeking spiritual realization, mental clarity, stress navigation, or consciousness understanding, Patanjali's framework offers proven guidance developed through centuries of application and refinement.